In 2015, the Kumars of Lucknow relied on public transport and an old scooter for their daily commute. Sanjay Kumar, a schoolteacher, and his wife, a small business owner, wished to buy a car—not just for comfort, but as a symbol of socioeconomic capital. Finally in 2023, after years of careful savings out of increased earnings, they proudly drove home a brand-new SUV. Their purchase meant more than just a transaction in national accounts — it was a testament to India’s evolving middle class, where aspirations have started turning into reality.

Discussions about India’s political economy often circle back to the notion that “the middle class is overlooked”. To defend or oppose this hypothesis, one needs to first define who belong to the middle-class. According to a 2021 report, 31 percent of the population who earn between 5 and 30 lakhs per annum, comprise the Indian middle class. The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey, on the other hand, suggests the middle 30 percent only spend around 2.3 lakhs annually. In response to the ambiguity in the definition of middle class, a 2012 Carnegie Endowment paper suggested a novel index – the Car Index. The underlying idea is that the middle class represents those who possess income beyond a certain threshold that allows them to purchase non-essentials like vehicles.

Understanding the car ownership metric

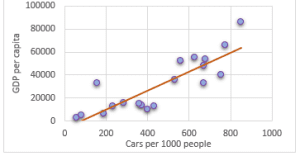

There is a positive relationship between per capita car ownership and per capita income levels – shown in Figure 1. The economic rationale is guided by Engel’s Law which states that as households become more affluent, the proportion of their income spent on necessary items declines, freeing up disposable income for discretionary spending. As nations move from low- to middle-income, the income elasticity of car ownership increases and eventually declines as they transition to high-income. In other words, car ownership grows faster than output in the middle-income stages. The macro-level transition mirrors the household-level dynamics, i.e., a higher share of middle-income households bolsters vehicle ownership in the country.

Figure 1: Car ownership (for every 1000 people) and GDP per capita of G20 countries

Source: World Population Review and IMF

Over the 2012-22 decade, number of registered motor vehicles in India grew at a CAGR of 8.3 percent, notwithstanding the pandemic. The CAGR of GDP was only around 5.5 percent during the same period, delineating income elastic car ownership. It might be argued that richer households played a significant role in this, given their capacity to purchase more than 1 vehicle. However, the CAGR of two-wheelers was also around 8.6 percent, indicating robust entry of lower-income buyers. Moreover, given the relatively low proportion of the rich in developing countries, their additional purchases can be safely absorbed into the margin of error of calculations. The projected CAGR of 3.1 percent in the second-hand car market further ensures that car ownership has picked up at lower levels of the income distribution.

The Prospering Middle in India

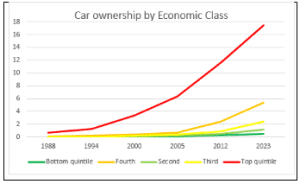

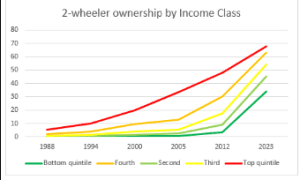

Further inspection of vehicle ownership reveals interesting trends about economic mobility. Over this last decade, car ownership has increased to 2.2-2.8x for the middle classes (3 middle quintiles) but only to 1.5x for the top quintile. During this same period, 2-wheeler ownership has increased over 9x for the bottom quintile, more than doubled for the middle classes and increased to only 1.4x for the top quintile. The conspicuously high difference between income classes indicates a structural transformation. Greater growth in vehicle ownership of middle-classes vis-à-vis the rich implies upward economic mobility – people have been able to meet their aspirations through higher income and employment.

Figure 2: Car and 2-wheeler ownership by income classes

Source: Data for India

Alternatively, if vehicle ownership is considered as an indicator of being middle-class, then the size of the middle class has grown. In the 2 years after the pandemic, passenger vehicles sales increased by 40 percent while 2-wheeler sales increased by 32 percent. Two forces are at action – the entry into middle class through purchase of 2-wheelers and upward movement within the middle class through purchase of 4-wheelers. Figure 2 shows how growth in two-wheeler ownership has been steeper than that in cars. This indicates that entry into the middle-class is faster than the transition to higher middle-income status – a phenomenon which is also seen across nations, leading to the issue of middle-income traps. The move to higher income levels is further corroborated by the fact that around 24.82 crore Indians escaped multidimensional poverty over the last 9 years.

Even among 4-wheeler purchases, there has been a distinct shift in preferences towards higher quality, more expensive cars. In the last 4 years, the share of Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs) in the market has doubled, dominating over half the market now. This can be attributed to higher disposable incomes, as well greater access to credit. Scheduled commercial bank credit for vehicle loans has more than doubled since January, 2019. However, the post-pandemic period saw relatively higher interest rates, making financing more costly. Rise in vehicle sales backed by auto loans indicates consumer confidence and increased purchasing power to offset future interest costs. Thus, it can be argued that the Indian middle class is growing, is richer and is confident about their future prospects.

Challenges Remain

While India has performed exceptionally in the post-pandemic period, as indicated by the Car Index, it is yet to catch up with developed nations. India has the lowest number of cars per capita among the G20 nations, while it performs much better in terms of two-wheelers. This could be due to two reasons. First, the relative price of cars is higher, suggesting that India is only in the initial stages of structural transformation. Second, besides affordability, consumers choose 2-wheelers for convenience. Traffic congestion and high commute times discourage 4-wheeler usage, as it also raises fuel consumption. These problems require long-term strategies for resolution.

The incentivisation of electric vehicles can assuage the concerns about increasing fuel cost. Greater access to finance in rural India can lower the relative cost of 4-wheelers and encourage new entrants. Maintaining the momentum in development of national roads and highways is imperative to make personal vehicles a viable choice. However, it should be noted that greater vehicle sales is just a metric. To boost that parameter, real, inclusive growth should be the means and the end.

Bio: Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation, specializing in macroeconomics, development, and labor market dynamics. He is dedicated to influencing policy discourse through his research and writing on economic policies and their implications.