The recent political colouring of India’s autonomous institutions, fueling the democratic framework since independence, for almost eight decades, has been rather unfortunate. The Election Commission of India, in the larger scheme of things, is one of the most critical bedrocks of India’s democracy, and therefore, to drag it into a political slugfest without an iota of substantiation is condemnable.

When it comes to the Election Commission of India, the transparency, integrity, verifiability, and accountability of the processes leave little room for doubt. These processes have evolved across generations and elections, moving from an analogue to a digital age.

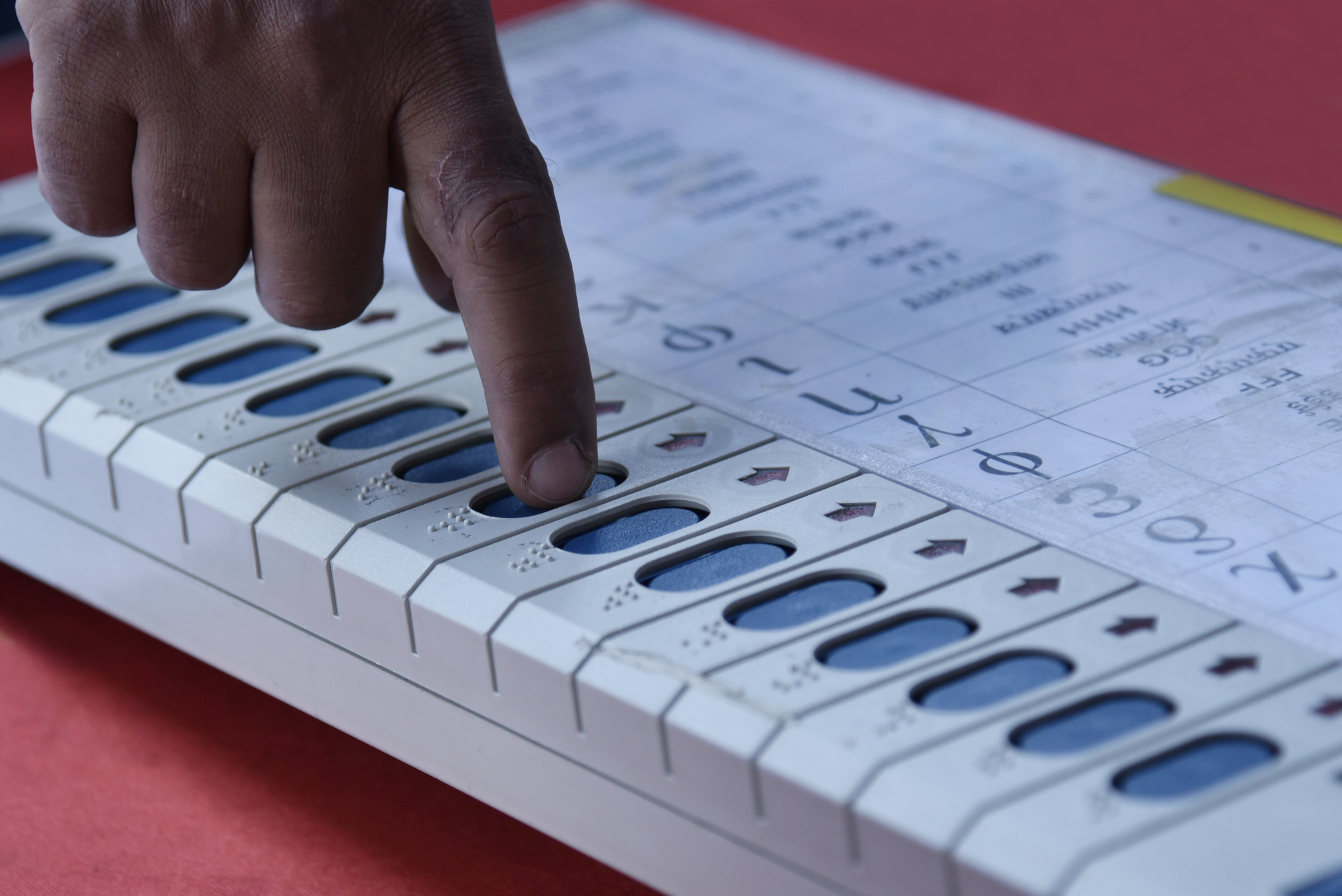

As a nation of almost a billion electors, we have all the reasons to be proud of the transition we have made from the ballot boxes to the EVMs, and all this, while ensuring the health and integrity of our elections, and this is where it becomes imperative to set the facts aside from the fiction being peddled.

Electors versus Voters

The fictitious arguments peddled in recent months have been devoid of facts, even at the foundational level. The definition of electors and voters has been confused, and rather lazily and incorrectly, the two terms have been used interchangeably.

Electors are those who are registered to vote. Voters are those who turn up to vote. Therefore, every voter is an elector, but not every elector is a voter.

In the 2024 Maharashtra Legislative Assembly elections, out of approximately 9.7 crore registered electors, 6.41 crore voters exercised their franchise, marking a turnout of 65.05 per cent, the highest in three decades.

Similarly, the 2023 Karnataka Assembly polls saw 5.21 crore electors, with 3.85 crore turning out to vote at an impressive 73.84 per cent turnout, the highest ever recorded in the state’s history, reflecting heightened enthusiasm amid a fiercely contested three-way battle.

Fast-forward to the 2025 Delhi Assembly elections, where 1.55 crore electors were on the rolls, but only about 0.94 crore cast their votes, yielding a 60.42 per cent turnout, the lowest among these recent polls and highlighting persistent challenges in urban voter mobilisation.

Nationally, the 2024 Lok Sabha elections dwarfed these figures, with 97.8 crore electors and 64.2 crore voters participating at a 66.10 per cent turnout.

These numbers are important. Firstly, an elector registered in multiple places does not amount to a voter in multiple places. The indelible ink, also known as the electoral ink, is a mechanism to ensure no one votes twice. Therefore, multiple registrations of a single elector cannot be claimed as multiple instances of voting by the same elector.

How Do Electoral Rolls Work?

The updating of the electoral rolls is the responsibility and the prerogative of the Election Commission of India. The SSR (Special Summary Revision) is done every year. An annual exercise, this allows the electors to update their personal details. For instance, if someone was a voter in Delhi in 2024 but has moved to Mumbai in 2025, they can apply for a change in constituency. The change will eventually reflect in the SSR published for 2025. The SSR happens every year, irrespective of when the election is.

Similarly, Special Intensive Revision (SIR), in motion in Bihar currently, is the prerogative of the ECI. The Bihar SIR witnessed the publication of a draft electoral roll, inviting parties and citizens to raise discrepancies, if any. The ECI, transparent as always, published a daily brief notifying the number of objections raised by the political parties. Interestingly, the parties questioning the integrity of the electoral rolls raised no objections when the draft rolls were published in Bihar.

In the last few months, several political factions have tried to create an impression that parties get access to the electoral rolls only after the elections are completed. This is incorrect. Between the publication of the draft roll and the last date of filing one’s nomination, the political parties, their booth level agents, and the electors have anywhere between three to six months to request changes, raise objections against insertions or deletions.

Take the example of the Karnataka Assembly Elections in 2023. On November 9, 2022, the draft electoral rolls were published, encompassing almost five crore electors. The following month, claims and objections were received from the stakeholders (from electors to political parties). While the election was in May, the final roll was published on January 5, 2023. However, the updating of the electoral rolls continued through Form 6, 7, and 8.

In the Indian electoral system, Form 6 serves as the application for the inclusion of a name in the electoral roll, enabling eligible individuals, such as first-time voters turning 18, those shifting from another constituency, or overseas Indians, to register and obtain a Voter ID card, thereby expanding the democratic base.

Form 7, on the other hand, is used to object to the inclusion of a name or request the deletion of an existing entry, typically for reasons like the death of a voter, relocation outside the area, or identification of duplicates, helping maintain the accuracy and integrity of the rolls by removing ineligible entries.

Finally, Form 8 facilitates corrections to existing details in the electoral roll, such as updating a misspelt name, address, gender, or photograph, ensuring that voter records remain current and reflective of personal changes without requiring full re-registration.

In Karnataka, the election was announced on March 29, 2023, and the last date for nomination filing was April 20, 2023. The cutoff date for nomination filing is the last date for the electoral roll updating. Thus, in Karnataka, the electors, the parties, and the commentators had almost 160 days or 22 weeks to raise any objections against the electoral rolls.

Why the Booth Level Agents are Indispensable

Taking the example of Karnataka forward, the final elector count was approximately 5.2 Crore, with 3.8 Crore turning up to vote, across more than 58,000 booths. That puts an average of 900 electors and 660 voters per booth. This is where the role of the booth-level agents (BLAs) becomes important.

Most national and regional parties, given their political capital in a state, have a booth coverage of 75 to 90 per cent. Their BLAs, working along with booth-level officers, have access to the electoral rolls for almost 22 weeks.

Given how booth-level management works in politics, one can assume that the booth-level agents would easily detect any large-scale omission or deletion in the electoral rolls. To scan through a thousand names across four to five months (on average) should not be a herculean task.

Booth-level agents have an important role to play on the election day as well. Booth-level agents, specifically the polling agents appointed by political parties or candidates to monitor proceedings inside the polling station, sign Form 17C (Part I) alongside the Presiding Officer.

Form 17C Part I is prepared at the close of polling by the Presiding Officer, who fills in details like total electors, votes polled (including EVM, postal, and tendered ballots), and invalid votes. Both the Presiding Officer and the polling agent(s) then sign it to authenticate the account before it’s sealed and stored with the EVMs. A copy is handed to each polling agent for verification.

Therefore, if an unprecedented inclusion happens on any of the booths, the polling agents would notice. Given that the average elector size of a polling booth is one thousand, unprecedented addition or deletion cannot be attempted. The final step of the electoral process validates the steps before. Think of it as the loop of verifiability, where each block serves as evidence of the integrity of the preceding block.

The Burden of Proof

For the last few years, many factions have faulted the EVMs being deployed during the national and state elections. However, there is not a single instance of any accusation being proven. The new set of allegations will meet the same fate. The process is crystal clear. There are too many stakeholders. And there is no dearth of time.

Rhetoric will not discredit the ECI, for its processes are far too formidable. Facts above fiction. Reason above rhetoric.