A remarkably preserved 37,000-year-old bamboo fossil discovered in Manipur’s Imphal Valley has offered new insights into how Asian bamboo species survived the harsh Ice Age. The fossil, found in the silt-rich deposits of the Chirang River, carries distinct thorn scars—an extremely rare feature almost never preserved in geological records.

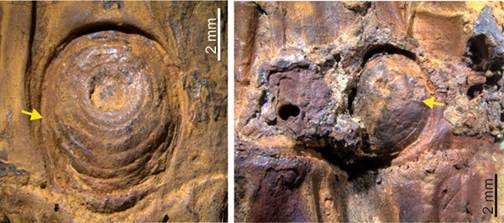

Researchers from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), an autonomous body under the Department of Science and Technology, stumbled upon the fossilised bamboo stem during a field survey. Detailed lab analysis revealed that the markings on the stem were ancient thorn scars, allowing scientists to identify it as belonging to the genus Chimonobambusa.

Bamboo fossils are rarely found because the plant’s hollow and fibrous structure decomposes quickly. The preservation of thorn scars, buds and nodes in this specimen makes the find exceptional. According to the researchers, this is the earliest known evidence of thorny bamboo in Asia.

Scientists compared the fossil’s structure with modern species such as Bambusa bambos and Chimonobambusa callosa to reconstruct its defensive features and ecological role.

Their study suggests that while Ice Age climatic conditions — marked by cold and dryness — led to the disappearance of bamboo from regions like Europe, parts of Northeast India functioned as a natural refuge where bamboo could continue to survive.

Published in the journal Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, the study highlights that the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot served as an important shelter for plant life during periods of global environmental stress. The findings also provide valuable clues to understanding bamboo evolution and palaeoclimatic conditions in Asia.

The research team—H. Bhatia, P. Kumari, N.H. Singh and G. Srivastava—said the discovery expands knowledge about how ancient plant species adapted to changing climates and underscores Northeast India’s ecological significance.