An immune- and cancer cell-targeting antibody therapy has shown potential to eliminate residual traces of multiple myeloma, a deadly blood cancer, according to interim results from a clinical trial.

The trial involved 18 patients who received up to six cycles of the bispecific antibody linvoseltamab. Highly sensitive tests revealed no detectable disease in any of the participants, according to findings presented at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting in Orlando, US.

The early success suggests that linvoseltamab could help patients avoid bone marrow transplants, which require intensive chemotherapy, and may improve long-term outcomes against the disease.

“These patients received modern, effective upfront treatment that eliminated 90 per cent of their tumor,” said lead researcher Dickran Kazandjian, from the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine.

“Typically, patients like these would undergo high-dose chemotherapy and a transplant. Instead, we treated them with linvoseltamab,” Kazandjian added.

Researchers described the results as “extremely impressive,” noting that the disappearance of lingering myeloma cells could significantly benefit patients’ futures. While the therapy can keep the disease at bay for years, recurrence remains a possibility.

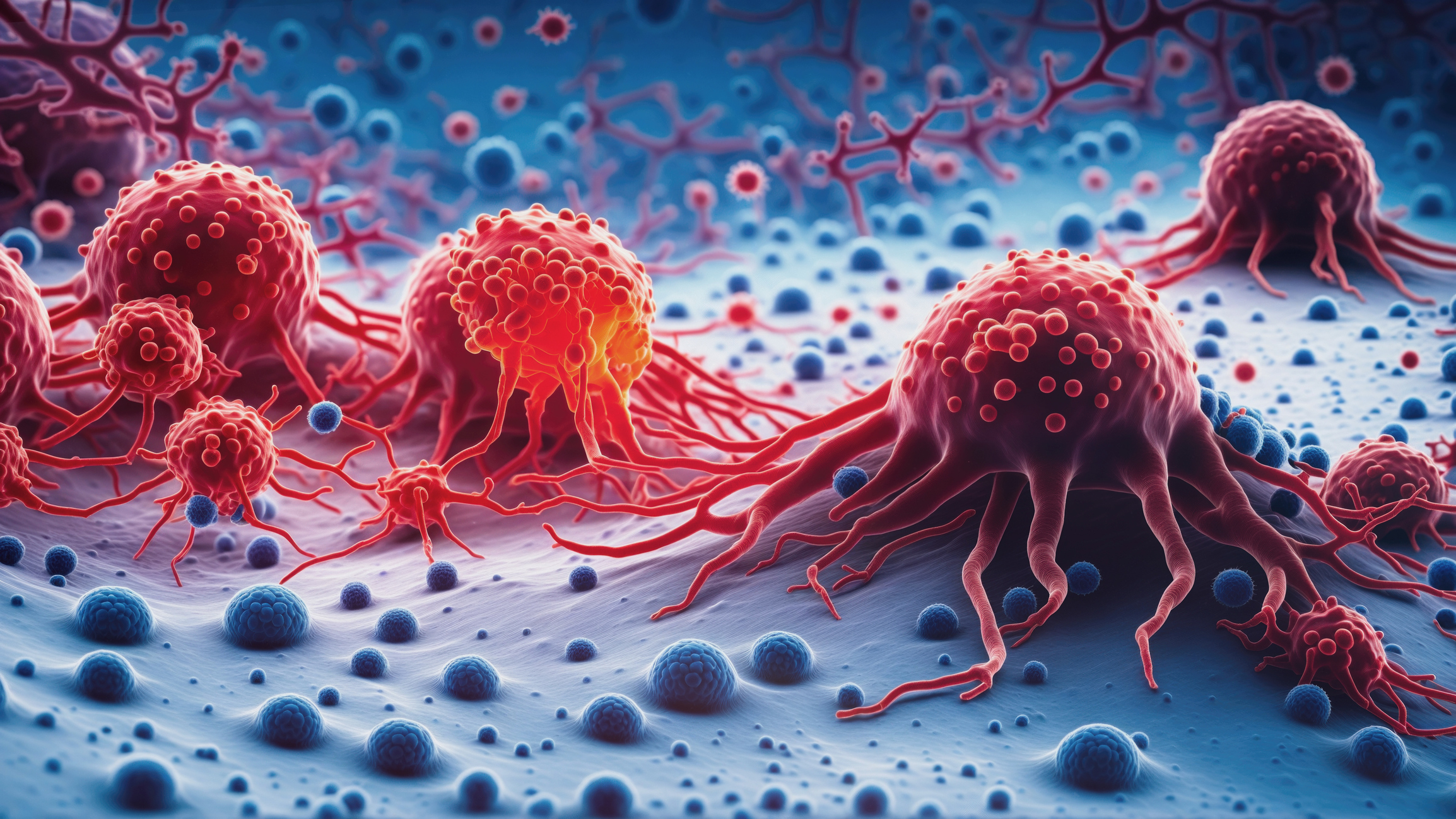

Multiple myeloma originates in antibody-producing plasma cells. These cancerous cells accumulate in the bone marrow, interfering with normal blood cell function and causing damage. Currently, there is no established cure.

Linvoseltamab works by binding to CD3, a protein on T cells that attack cancer cells, and BCMA, a protein found on multiple myeloma cells. By bringing these cells into contact, the antibody stimulates the body’s immune response against the cancer.

Some patients experienced side effects, including neutropenia (a drop in white blood cells) and upper respiratory infections, but all events were within acceptable safety limits, according to Kazandjian.

Given its performance so far, researchers hope linvoseltamab may offer more durable responses than transplants, potentially providing long-term disease control or a “functional cure.”

(IANS)